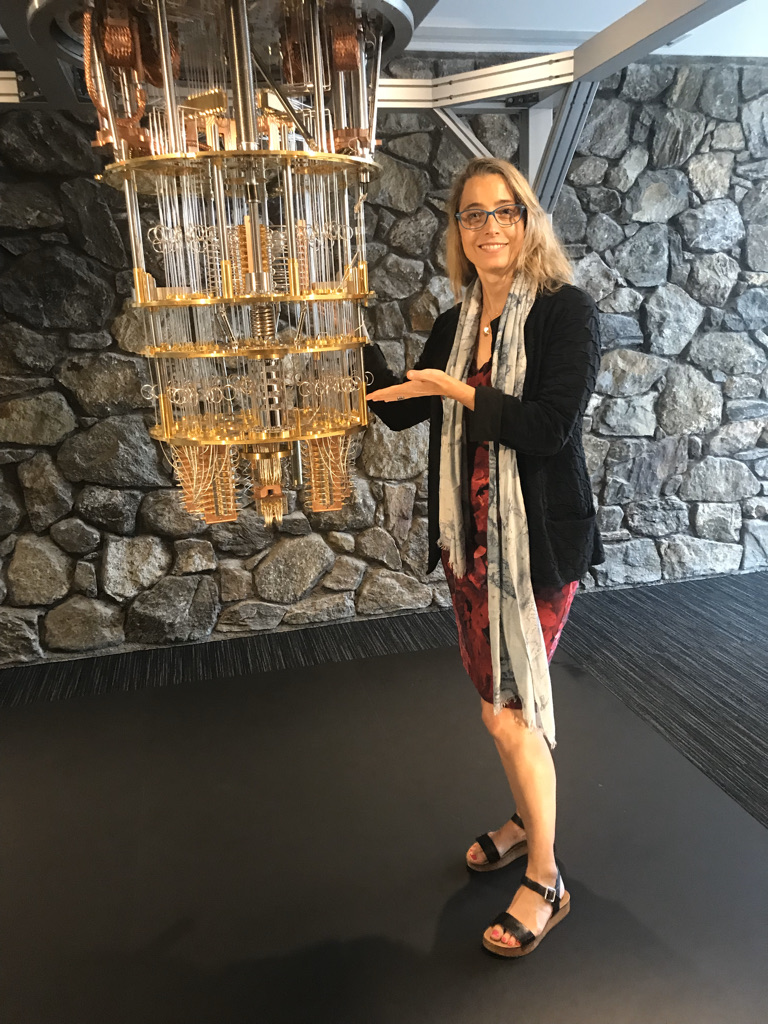

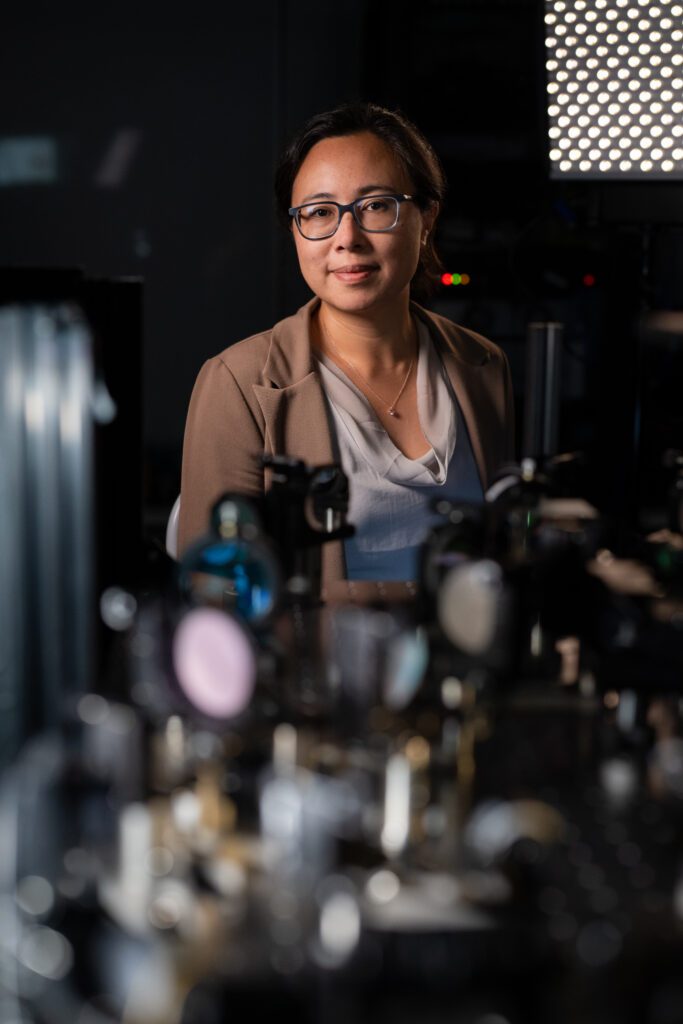

Interview with Dr. Nathalie P. de Leon, Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, at Plasma Physics Laboratory, Princeton University

Beyond beauty and rarity, diamonds have been used by scientists due to their exceptional hardness and resistance to pressure to build instruments like ultra-thin knives for electron microscopy samples, or in powders to polish materials. However, diamond’s quantum properties have also been shown to be crucial for cutting-edge applications, sometimes even if they are impure, those that would be rejected in the jewelry business.

We interviewed Nathalie P. de Leon, a physicist leading a research group in Princeton, New Jersey, that turns pure diamonds into defective diamonds to push the frontiers of quantum applications, such as quantum computers, sensors, and communication networks.

“What we do is that we kick out one or two carbons of the diamond and replace it with something else, then we get a little defect that responds to light in a different way than the carbons,” Nathalie explains. “The interesting aspect about these imperfections, in the quantum world, is that some of them have high efficiency in the sense that they absorb a photon and then spit a photon back out, so that they act as single photon sources.”

These “imperfections” are called color centers, tiny defects placed with atomic precision inside the diamond’s crystal, causing the diamond to behave like a single atom from a quantum perspective. What others call a flaw, Nathalie sees as a priceless feature.

“The term ‘color center’ is very old; it is really just about shining light that gets absorbed and light that gets emitted; then, the color center is what makes the diamond look yellow or blue. These color centers are defects in the diamond that give us very localized quantum states that we can use in many applications.”

Building Quantum Devices from Flawed Diamonds

Nathalie uses nitrogen to replace the carbon vacancies to create her color centers, called “NV centers.” Then, she and her team manipulate and measure quantum properties of the NV center’s electrons with extraordinary precision. One of these manipulable quantum features is the electron’s spin. The spin is a fundamental quantum-mechanical property found in elementary particles, such as electrons and quarks, and in composite particles, such as protons and atoms, that can have specific values. For example, the electron’s spin can have two values that physicists call “spin up” and “spin down” (or ½ and – ½ ), and it is responsible for the magnetic properties of the electron.

Unlike most quantum systems, which must be kept at extremely low temperatures, NV centers in diamonds can operate at room temperature, a rare advantage in emerging quantum technologies that desperately need long coherence times (the time the system can maintain a quantum state). This unique property makes them among the few quantum platforms that can operate outside specialized cryogenic environments (extremely cold temperatures), opening the door to practical quantum technologies.

“The main reason why these NV centers are really exciting is the very long spin coherence time, the longest coherence time anyone has ever measured at room temperature and ambient conditions, so you have milliseconds of coherence time, which is really remarkable because you can use the electron’s spin up or down to store quantum information. It also has very efficient optical transitions, which means I put one photon in and get one photon back out.”

Diamonds, Light, and the Quantum Frontier

Nathalie’s research lab has shown that these engineered diamonds are more than just scientific curiosities—they can serve as information storage and processing devices, sensors, and building blocks for quantum communication. De Leon focuses on using NV centers as quantum sensors to measure magnetic fields with extremely high precision and spatial resolution, opening a new frontier in which quantum sensors can help us discover new materials, perform biomedical diagnostics, and aid navigation. Her lab works on the full gamut from basic research to applied technologies, innovating diamond growth in collaboration with Alastair Stacey at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, devising new sensing schemes, and making integrated sensing devices.

In a 2022 Science paper, her group showed that NV centers could be used to directly measure correlations in magnetic noise, a new physical quantity that is not measurable by any instrument today. A follow-up paper (in press in Nature) showed how entanglement can be harnessed to improve these measurements. In a 2025 paper in Physical Review X, Nathalie and her team report a breakthrough in studies of nitrogen color centers in diamonds. Traditionally, researchers could study only one diamond color center at a time—a slow process that limited what they could learn about collective quantum behavior. De Leon’s group changed that, creating a system that can read signals from hundreds of nitrogen vacancy centers simultaneously.

With this innovation, scientists can create tools that can track how tiny magnetic fields vary not just at single points, but across entire 100-micrometer-scale regions. These tiny devices could help advance the study of exotic materials or the development of medical instruments.

Science as a Game of Risk

For Nathalie, research is about strategic exploration. After she showed how to control the surface of diamond to make near-surface NV centers behave well, she started a new collaboration with Andrew Houck and Bob Cava to tackle a completely different platform—improving the quantum coherence of superconducting qubits, which had been stagnant for about a decade despite enormous worldwide investment. In five years, this collaboration has yielded two major improvements in superconducting qubit coherence, first from 100 microseconds to 300 microseconds (Nature Communications 2021), and then to over 1.5 ms (Nature 2025). Jumping into a new effort required devising a large-scale, interdisciplinary playbook to measure and tackle many different aspects of the qubit at once, which she describes in a recent 2025 Nature Physics comment. She compares it to playing Risk, the board game where players place pieces, roll dice, and attempt to conquer new territories. In her view, science works in a similar way.

“You can think of many of these projects as a giant Risk board game. What we are doing is placing forces in different parts of the board because we want to advance the state of the art in some technology. We created qubits made with tantalum and achieved a factor-of-three improvement over the state of the art. And then, we ask, can we do better? And I also need to be aware of the different forces and that other people are working on a different part of the game. For example, now we have one millisecond of coherence, so, how can we make that into 10 milliseconds? We have efforts tackling new materials and better fabrication, but also on packaging and filtering, understanding when the coherence is worse than the loss, measuring time variation… The frontier does not care about what instruments we already have in the lab or what knowledge I have in my head. So, we spend a lot of time figuring out how we are going to solve that problem and advance on the board.”

From blowing up things in her parents’ garage to Harvard, Princeton, and beyond

As a child, de Leon’s curiosity stretched in every direction—from music and art to debate and journalism. But beneath all those interests was a restless fascination with how the world worked. Growing up in a place with few outlets for kids drawn to science, she pursued science as a hobby at home, mixing chemicals and experimenting with crystal growth—sometimes a little too enthusiastically.

“I was mixing chemicals in my garage. I almost blew my fingers a couple of times,” she laughs. “I was interested in crystal growth; I found that exciting, the purification and patience, and I still have a fondness for crystal growth.”

What began as a love for crystals evolved into a career uncovering the quantum secrets hidden inside them, a trajectory that has been anything but linear. From chemistry at Stanford to a PhD in chemical physics at Harvard University, by the time de Leon reached graduate school, her path had already begun to twist in unexpected directions.

De Leon joined as an assistant professor at Princeton in 2016. Since then, she’s earned a collection of early-career honors—from the U.S. Department of Energy, DARPA, and the National Science Foundation—as well as a Sloan Research Fellowship. She was also awarded the APS Landauer-Bennett Award in 2023 for her work in quantum computing. Currently, she is an Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Princeton University, a co-Director of the Princeton Quantum Initiative, and an associated faculty member of physics, as well as at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. She is also a Visiting Research Faculty at Google Quantum AI. With her research, Nathalie helps bridge the gap between fundamental physics and engineering.

“These are very exciting times to be living through,” Nathalie concludes.

De Leon publications to deep dive into her research

- De Leon, N. (2025). How to build a long-lived qubit. Nature Physics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-025-03044-y

- Cheng, K., Kazi, Z., Rovny, J., Zhang, B., Nassar, L. S., Thompson, J. D., & De Leon, N. P. (2025). Massively multiplexed nanoscale magnetometry with diamond quantum sensors. Physical Review X, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1103/t8fz-3tzs

- Rose, B. C., Huang, D., Zhang, Z., Stevenson, P., Tyryshkin, A. M., Sangtawesin, S., Srinivasan, S., Loudin, L., Markham, M. L., Edmonds, A. M., Twitchen, D. J., Lyon, S. A., & De Leon, N. P. (2018). Observation of an environmentally insensitive solid-state spin defect in diamond. Science, 361(6397), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0290

- “Millisecond lifetimes and coherence times in 2D transmon qubits,” M. P. Bland, F. Bahrami, J. G. C. Martinez, P. H. Prestegaard, B. M. Smitham, A. Joshi, E. Hedrick, S. Kumar, A. Yang, A. Pakpour-Tabrizi, A. Jindal, R. D. Chang, G. Cheng, N. Yao, R. J. Cava, N. P. de Leon, A. A. Houck, Nature (2025).

- “New material platform for superconducting transmon qubits with coherence times exceeding 0.3 milliseconds,” A. P. M. Place, L. V. H. Rodgers, P. Mundada, B. M. Smitham, M. Fitzpatrick, Z. Leng, A. Premkumar, J. Bryon, A. Vrajitoarea, S. Sussman, G. Cheng, T. Madhavan, H. K. Babla, X. H. Le, Y. Gang, B. Jaeck, A. Gyenis, N. Yao, R. J. Cava, N. P. de Leon, A. A. Houck, Nature Communications 12, 1779 (2021).

- “Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware,” N. P. de Leon, K. M. Itoh, D. Kim, K. K. Mehta, T. E. Northup, H. Paik, B. S. Palmer, N. Samarth, S. Sangtawesin, D. W. Steuerman, Science 372, 6539, eabb2823 (2021).

- “Nanoscale covariance magnetometry with diamond quantum sensors,” J. Rovny, Z. Yuan, M. Fitzpatrick, A. I. Abdalla, L. Futamura, C. Fox, M. C. Cambria, S. Kolkowitz, N. P. de Leon, Science 378, 6626 1301-1305 (2022).