The authors of a new book tell the stories of 16 women who made crucial contributions to quantum physics, yet whose names don’t usually appear in textbooks

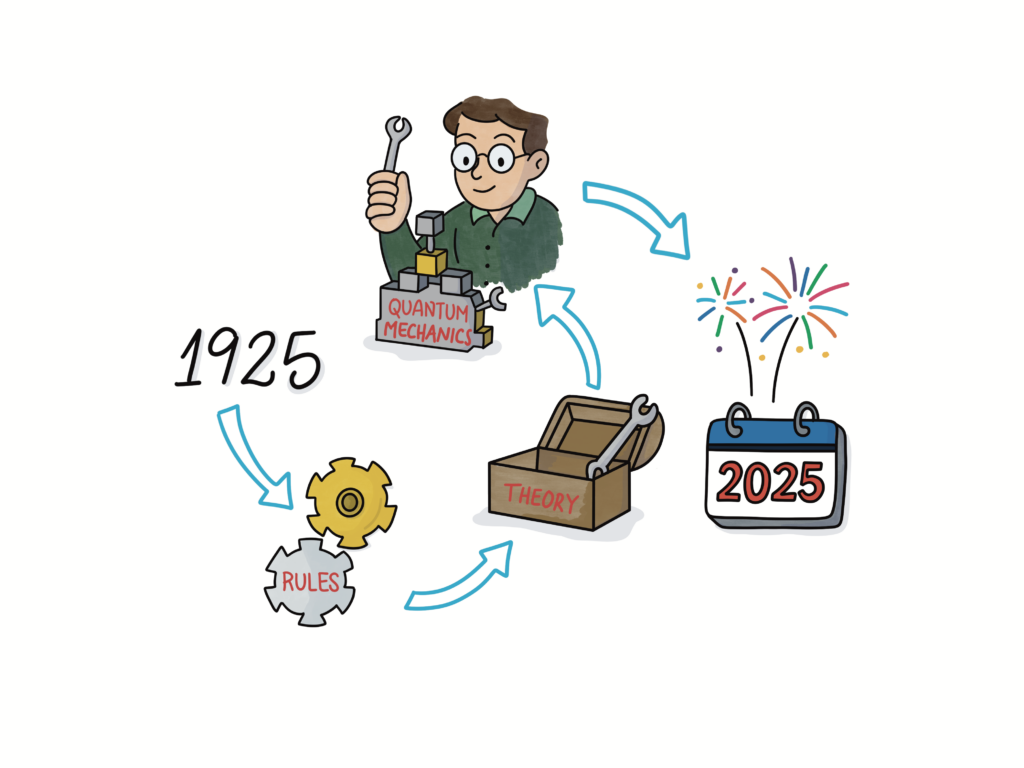

As modern quantum mechanics was taking shape in the mid 1920s, the field was sometimes referred to in German as Knabenphysik—“boys’ physics”—because so many of the theorists who were crucial to its development were young men. A new book published as part of the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology pushes back against that male-dominated perspective, which has also tended to dominate historical analyses. Coedited by historians of science Daniela Monaldi and Michelle Frank, physicist-turned-science writer Margriet van der Heijden, and physicist Patrick Charbonneau, Women in the History of Quantum Physics: Beyond Knabenphysik presents biographies of 16 oft-overlooked women in the field’s history.

The editors did not profile physicists such as Lise Meitner and Maria Goeppert Mayer, who have attracted significant attention from historians and physicists. As the editors explain in the book’s introduction, focusing on a few heroic figures perpetuates “a mythology of uniqueness.” They instead highlight individuals who are lesser known but nevertheless made important contributions. The following photo essay highlights six of those scientists.

H. Johanna van Leeuwen

In 1919, Dutch physicist H. Johanna van Leeuwen (1887–1974) discovered that magnetism in solids cannot solely be explained by classical mechanics and statistical mechanics: It must be a quantum property. Niels Bohr had made the same insight in his 1911 doctoral thesis, but he never published the result in a scientific journal; it was published only in Danish and barely circulated outside Denmark. Van Leeuwen rediscovered what is now called the Bohr–Van Leeuwen theorem in her doctoral research at Leiden University. The theorem, which has applications in plasma physics and other fields, came to the attention of the broader community after Van Leeuwen published an article based on her doctoral thesis in the French Journal de Physique et le Radium (Journal of Physics and Radium) in 1921.

As happened with many women of that era, little trace was left of Van Leeuwen (pictured here in an undated photo) in the historical record. Chapter authors Van der Heijden and Miriam Blaauboer uncovered several sources that helped them assemble an illustrative synopsis of her career. Van Leeuwen was one of four women to study with Hendrik Lorentz, with whom she remained close until his death in 1928. Unlike many women of her generation, Van Leeuwen remained in the field for her entire career: She was appointed as an assistant at the Technical College of Delft in 1920, a position that required her to supervise laboratory courses for electrical engineering students. In the little spare time she had, Van Leeuwen continued her research into magnetism. In 1947, she was promoted to reader, which meant that she could finally teach her own courses.

Laura Chalk Rowles

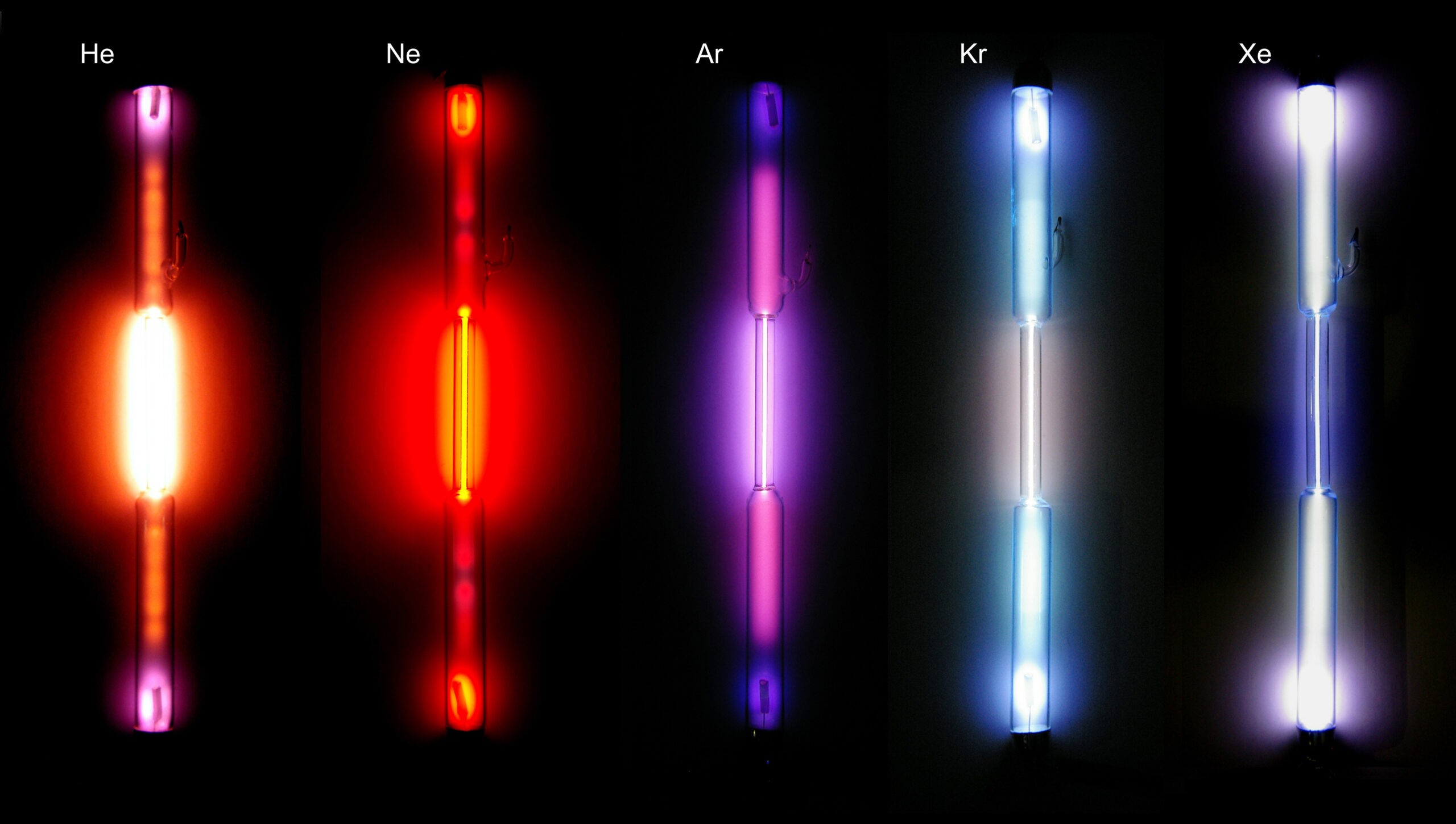

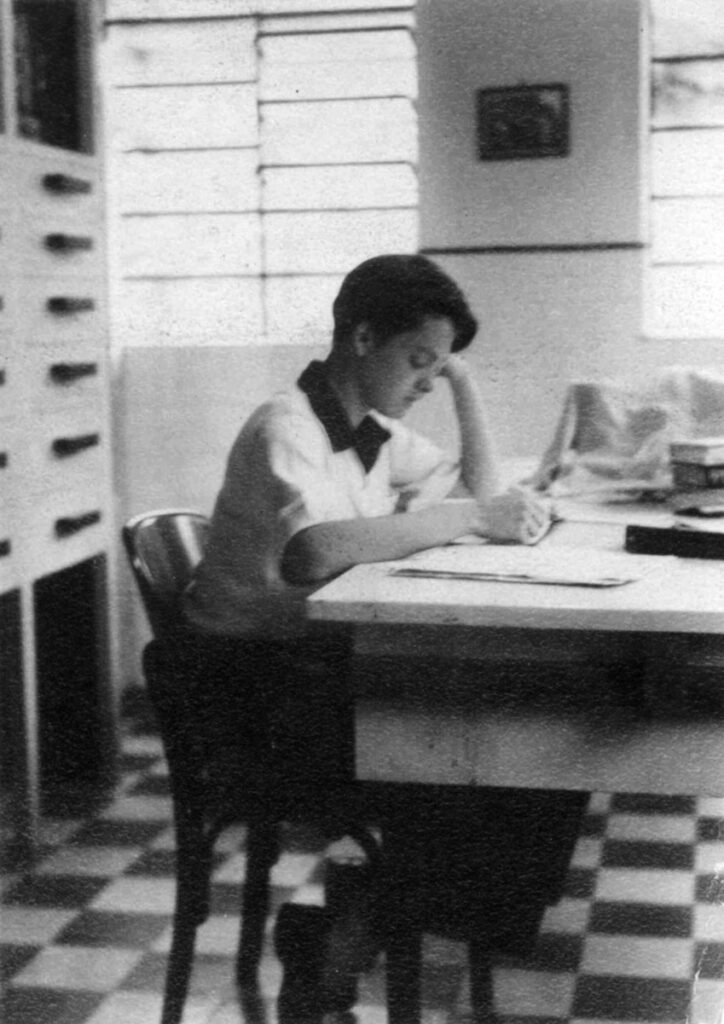

Laura Chalk Rowles (1904–96) was one of the first women to receive a PhD in physics from McGill University in Montreal, in 1928. Her dissertation investigated the Stark effect—the shifting of the spectral lines of atoms exposed to an external electric field—in the hydrogen atom. In his series of 1926 articles on wave mechanics, Erwin Schrödinger had used quantum theory to predict how the Stark effect would affect the intensities of the Balmer series of spectral lines in hydrogen. As chapter author Daniela Monaldi outlines, Chalk (pictured ca. 1931) used an instrument known as a Lo Surdo tube to measure the intensities of the spectral lines; the work provided the first experimental confirmation of Schrödinger’s predictions. She published several articles on the subject in collaboration with her adviser, John Stuart Foster.

Later in his life, Foster regarded his subsequent work on the Stark effect in helium as more important than the hydrogen experiments he had carried out with Chalk. Observers and historians have tended to follow his lead, so her contributions are often overlooked. After spending the 1929–30 academic year at King’s College London, Chalk received a teaching position in McGill’s agriculture college. But after she married William Rowles, who was also at McGill, she scaled back to working only part time. Five years later, she was let go because of rules that were ostensibly designed to prevent nepotism but typically served to exclude women from the professoriat.

Elizabeth Monroe Boggs

Elizabeth Monroe Boggs (1913–96) received significant press attention for her advocacy work on behalf of people with disabilities. But her prior career in science has long gone overlooked, writes chapter author Charbonneau. Boggs (pictured in 1928) was the only undergraduate to study with famed mathematician Emmy Noether at Bryn Mawr College before Noether’s untimely death in 1935. After graduating, Boggs pursued a PhD at the University of Cambridge, where she began studying the application of quantum physics to molecular structure—a pursuit that is now known as quantum chemistry. For her thesis, she used an analog computing device called a differential analyzer to probe the wave functions of diatomic molecules.

After finishing her studies, she received a research assistantship at Cornell University, where she met and married chemist Fitzhugh Boggs. As was common in the day, his career took precedence over hers: They moved to Pittsburgh in 1942 when Fitzhugh received a job at Westinghouse. Elizabeth taught at the University of Pittsburgh for a year and then got a job at the Explosives Research Laboratory outside the city, where she ended up contributing to the Manhattan Project by helping to design the explosive lens for implosion bombs like the one ultimately used on Nagasaki. She eventually decided to withdraw from the field and focus on advocacy after the birth in 1945 of a son, David, who had severe developmental delays because of brain damage from an illness.

Katharine Way

Katharine Way (1903–95) was the first graduate student of John Wheeler’s at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the late 1930s. As chapter author Stefano Furlan recounts, Way’s research during her PhD studies included using the liquid-drop model of the atom, which approximates the nucleus as a droplet of liquid, to examine how nuclei deform when rotating at high speeds. In a 1939 Physical Review article, she describes the magnetic moments of heavier nuclei. While carrying out the research, Way (pictured in an undated photo) noticed an anomaly that she brought to Wheeler’s attention: The model was unable to account for highly charged nuclei rotating at extremely high speeds. In later recollections, Wheeler regretted that the two didn’t further investigate that observation: He noted that, in retrospect, the model’s failure in that case was an early indication that nuclei could come apart, just as they do in fission.

During World War II, Way worked on nuclear reactor design at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago; she moved to Oak Ridge Laboratory in 1945. Along with Eugene Wigner, she published a 1948 Physical Review article outlining what is now known as the Way–Wigner formula for nuclear decay, which calculates rates of beta decay in fission reactions. She spent much of her postwar career at the National Bureau of Standards (now NIST), where she initiated and led the Nuclear Data Project, a crucial source for information on atomic and nuclear properties that is now part of the National Nuclear Data Center at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Way was also active in efforts to get nuclear scientists to think about the societal ramifications of their work.

Sonja Ashauer

Although her death from pneumonia at age 25 ended her career practically before it began, Sonja Ashauer (1923–48) was an accomplished physicist and promising talent, chapter authors Barbra Miguele and Ivã Gurgel argue. The daughter of German immigrants to Brazil, Ashauer (pictured ca. 1940) studied at the University of São Paulo with Italian physicist Gleb Wataghin, who likely introduced her to quantum theory. Shortly before the end of World War II, in 1945, she moved to the University of Cambridge, where she became the only woman among Paul Dirac’s few graduate students.

In her 1947 thesis, Ashauer worked on one of the most pressing problems of the day in quantum electrodynamics: what was termed the divergence of the electron’s self-energy. Because that self-energy—the energy resulting from the electron’s interactions with its own electromagnetic field—is inversely proportional to its radius, the value tends to infinity when the particle is modeled as a point charge. Ashauer attacked the problem by working to improve classical electrodynamics in the hope that it might inform the quantum theory. That divergence problem and others were ultimately solved through the renormalization techniques discovered around 1950.

Freda Friedman Salzman

Freda Friedman Salzman (1927–81) is more often remembered for her work advocating for women in science than for her significant contributions to physics. As an undergraduate, Salzman (pictured in the late 1940s) studied physics with nuclear physicist Melba Phillips at Brooklyn College. In the mid 1950s, in collaboration with her husband, George Salzman, she came up with a numerical method to solve the integral equations of what was known as the Chew–Low model: a description of nuclear interactions developed by Geoffrey Chew—Freda’s dissertation adviser at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—and Francis Low. To carry out those calculations, the Salzmans used the ILLIAC I, an early computer. Published in 1957 in Physical Review, what was soon termed the Chew-Low-Salzman method helped stimulate work by nuclear and particle physicists, including Stanley Mandelstam, Kenneth Wilson, and Andrzej Kotański in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Chapter author Jens Salomon argues that the method was one of Freda’s most important contributions to the field.

Freda and George lived an itinerant academic lifestyle for a period before finding what they believed to be permanent positions at the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1965. Four years later, Freda was fired after the university began to enforce what they claimed to be an anti-nepotism policy. Her termination became a cause célèbre, and after a long campaign, she got her job back in 1972 and received tenure in 1975. The fight to regain her job at the university appears to have motivated Salzman to devote increasing amounts of time to feminist advocacy in the 1970s.

From Physics Today